How Can You Have Impact in Your Current Job?

Written October 29 2024

Est. 40 minute read

This article draws heavily from 80,000 Hours (see their up-to-date entry here).

Introduction

The challenge with much self-help advice today is that it’s often grounded in minimal evidence. Take, for instance, the common suggestion to “think positively” to achieve your goals. This advice, shared by everyone from teachers to career experts, hinges on the idea that if you visualise your ideal future, you’ll be more likely to reach it.

However, recent research suggests that fantasising about your perfect life might actually reduce motivation, as it can make you feel like you’ve already achieved those goals. Similarly, in the Bible, we see examples where faith and action are intertwined. Nehemiah didn’t merely dream of rebuilding Jerusalem’s walls - he took action, praying and rallying people to work despite opposition. His faith drove him to practical, disciplined steps—an example of effective goal-setting rooted in commitment, rather than mere positive thinking.

There are a number of evidence-backed steps to increase productivity and career success. The advice we offer here is grounded in (i) empirical evidence, (ii) sound reasoning, (iii) potential for positive impact, (iv) broad applicability, and (v) low costs for trying. While the evidence isn’t perfect, these insights are the best we’ve found in over a decade of research.

The journey starts with building new habits—just as Nehemiah gradually built each section of the wall. Atomic Habits, a practical guide on habit formation, explains that new habits take about 30 days to establish. So rather than starting multiple habits, skim through the list of possible changes and choose one to commit to.

1. Don’t forget to take care of yourself

Before we go on to more complex advice, a reminder: ambitious people often don’t take care of themselves, which can lead to burnout and ultimately limit their success. In fact, even if you’re primarily focused on helping others, it’s crucial to take care of yourself. Professor Adam Grant found that altruists who also looked out for their own interests were more productive in the long term and ultimately made a greater impact.

As Christians, we’re called to honor the bodies God has given us. In 1 Corinthians 6:19-20, Paul reminds us, “Do you not know that your bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit, who is in you… Therefore honor God with your bodies.” When we respect our human limitations and care for ourselves, we’re honouring God’s gift of our bodies and maintaining the strength needed to fulfill His purpose.

To care for yourself, the most important thing is to focus on the basics: getting enough sleep, exercising, eating well, and nurturing close friendships and relationships. Research supports these essentials, showing they significantly impact happiness, health, and energy—often more than factors like income. So, if there’s an area where you can make an improvement, it’s worth prioritising it. Sometimes it’s about small tweaks, like using an eyemask for better sleep, but it often involves building consistent habits, like scheduling regular calls with a close friend.

Here are some specific suggestions:

Sleep: Lynette Bye’s guide summarizes research on how to improve sleep.

Exercise: Aim to meet the basic guidelines by the UK’s National Health Service.

Diet: Avoid processed foods and prioritise plants. Experiment with what sustains your energy best.

Friendships: Regular time with friends and connection to community such as a Church family strengthens well-being; we’ll offer more advice on this later.

For more practical insights, explore life hacks by Alex Vermeer or the Huberman Lab podcast, which summarises scientific research on sleep, exercise, diet, and energy management. In caring for ourselves, we’re not only preparing ourselves to do God’s work but are also honoring the temple of the Holy Spirit within us.

2. If helpful, make mental health your top priority

About 30% of people in their 20s have some kind of mental health problem.

If you’re suffering from a mental health issue — be it anxiety, bipolar disorder, ADHD, depression, or something else — then it’s often best to prioritise dealing with it or learning to cope better. It’s one of the best investments you can ever make — both for your own sake and your ability to help others.

We know many people who took the time to make mental health their top priority and who, having found treatments and techniques that worked, have gone on to perform at the highest level.

The CEO of 80,000 Hours has spoken about taking care of mental health as a major priority on this podcast.

If you’re unsure whether you have a mental health issue, it’s well worth investigating. We’ve also known people who have gone undiagnosed for decades, and then found their life was far better after diagnosis and treatment.

And don’t get hung up on whether you satisfy the criteria for a formal diagnosis. Many mental health conditions appear to lie on a spectrum (e.g. from good mood to ‘normal’ unhappiness to depression), and the point at which a formal diagnosis is made is ultimately arbitrary. What matters is not the label that’s applied, but whether you can find helpful ways to feel better.

Mental health is not our area of expertise, and we can’t offer medical advice. We’d recommend seeing a doctor as your first step. If you’re at university, there should be free services available.

This said, we’ve collected some of the resources we’ve personally found most helpful for you to explore.

Probably the most evidence-based form of therapy is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which has been found to help with many different conditions.

Moreover, managing your emotions is just a vital life skill for everyone, and CBT is one of the main evidence-based ways of getting better at that.

80,000 Hours interviewed a CBT therapist, Tim LeBon, about what CBT involves and why it might be useful to our readers.

80,000 Hours spoke with therapist Hannah Boettcher on the types of mental health issues people interested in effective altruism face, and the tools Hannah uses to address them in her therapy practice.

A classic book is Feeling Good by David Burns — reading the book has even been tested in randomised controlled trials and found to reduce the symptoms of depression.

Spencer Greenberg (who has also been on the 80,000 Hours podcast) developed an online CBT app that we like.

80,000 Hours has also written up a list of simple CBT-inspired questions you can ask yourself whenever something bad happens in your life — from struggling to find your keys to being in a car accident — and which will probably help you feel better and move on more quickly.

See the STOPP process for a quick CBT-based technique you can use to work with any difficult emotion.

Beyond the self-help resources above, for many conditions, speaking with a therapist is extremely beneficial. A key step is finding a therapist who’s a good match. Match is crucial — some research has suggested that the degree of ‘therapeutic alliance’ can even be more important than the form of therapy. This is often difficult, but here are some tips:

Ask for referrals from your friends whose judgement you trust.

Don’t feel like you need to stick with the first therapist you find. Most therapists will be happy to do an initial consultation or trial session, so you can do several of these and go with whoever has the best match.

Therapy can be roughly divided into two very different forms: those in the tradition of psychoanalysis, which aims to identify patterns of counterproductive behaviour starting in childhood, and those that are in the tradition of CBT, which tends to be practical and solution focused, and to have a clearer evidence base. Both forms can be useful, but our sympathies lie with the CBT tradition, so that’s what we’d suggest trying first. Make sure not to confuse the two types.

3. Deal with your physical health (not forgetting your back!)

Lots of health advice is snake oil. But it’s probably also the area where the most evidence-based advice exists. Besides your doctor, you can find easy-to-use summaries of the scientific consensus on how to treat different health problems on websites like the NHS’s Health A to Z and the Mayo Clinic. Read more about how to get evidence-based health advice.

We were surprised to learn that the biggest risk to our productivity is probably back pain: it’s a major cause of ill health globally, at least by some measures.

Repetitive strain injury (RSI) is also a hazard of modern workplaces, and can even permanently damage your ability to type or use a mouse.

Nevertheless, you can reduce your chances of back pain and RSI in a few ways:

Regularly change position (the pomodoro technique is useful).

Exercise regularly, probably including some strength training for the whole body (especially the posterior chain).

These steps sound trivial, but statistically, it’s pretty likely you’ll face a bout of bad back pain at some point in your life, and you’ll thank yourself for making these simple investments.

If you do get any symptoms, treat them immediately before they get worse. Read more about how to treat back pain and RSI.

4. Set goals

There is plenty of debate about the best ways to set goals. Should you focus more on outcomes or the process? Should your goals be ambitious or achievable?

These differences don’t matter too much. The key point is that setting goals works: people who set goals tend to achieve more.

So, what most matters is to get in the habit of setting goals for your personal development.

Longer-term goals

One place to start is to get clearer about what an ideal life would look like to you.

For example, how would your life ideally look in 10 years’ time? If money were no object, or you knew you couldn’t fail, how would you spend your time?

Don’t only think about what you’d like to achieve (many external achievements don’t seem to affect happiness that much), also think about your ideal “mundane Wednesday.” What exactly would you do from waking to falling asleep?

In doing this, it’s useful to keep in mind the ingredients that are normally most important for fulfilment:

Satisfying relationships e.g. with God, family, Church community, friends

Contributing to a goal beyond yourself e.g. serving others

Craft — something you feel competent in and find engaging (where you can enter a state of ‘flow’)

Some fun and positive emotion

A lack of major negatives, such as financial stress, health problems, or interpersonal conflicts

Goals for the year

In addition to (or instead of) your longer-term goals, consider setting 1–2 professional and 1–2 personal goals for the next year or quarter.

For instance, some people like to do an “annual life review.” A template for doing this that many on the 80,000 Hours team have found helpful is Alex Vermeer’s ‘8,760 Hours’document (no relation).

For your career, 80,000 Hours have also made this quick tool to help you reflect on your work once a year.

Learn to prioritise

A common pattern is that often most of the results come from the top couple of priorities. This is sometimes called the 80/20 principle — because about 80% of the results come from 20% of your activities.

This principle most likely applies to your goals, so it’s vital to put them in order of priority, and to focus all your attention on those at the top.

But life constantly throws more options at you, so this is an ongoing practice.

One exercise to help you do this is to make a list of your goals, pick the top couple, and then put everything below that on a do not do list.

If you want to think more about prioritisation, here are five frameworks.

It’s normal to always feel like you’re not doing enough. But if you’ve prioritised, and focus on your top priorities, then you’ll know you’re doing the best you can.

Now, once you’ve set some goals, how can you actually achieve them?

5. Try out this list of ways to become more productive

You can find lots of articles about which skills are most in-demand by employers — is it marketing, programming, or data science? But what people don’t talk about so often are the skills that are useful in all jobs; the ones that make you more effective at everything.

We’ve already covered several examples: how to build habits, prioritising, and taking care of yourself. Here we’ll cover another: building the habits of personal productivity.

Here’s an example: implementation intentions. Rather than saying “I will exercise every day,” define a specific trigger, such as: “When I get home from work, the first thing I’ll do is put on my trainers and go for a run.” This surprisingly simple technique has been found in a large meta-analysis to make people much more likely to achieve their goals — in many cases about twice as likely (effect size of 0.65).6

This section will also help you implement the rest of the advice in this article. Want to socialise more? Use a commitment device. Want to be more focused when you study? Batch your time. Want to take up gratitude journaling? Add it to your daily review.

What follows is a list of productivity techniques that have seemed most useful to the people we’ve worked with. This section is not particularly evidence-based, but we think that’s OK, because you can quickly try the techniques yourself and see if you get more done. Work through them one at a time for about a week each. Then spend several weeks on the ones that work for you until you’ve built the new habits.

Sticking to your goals

If you’re having trouble getting going, start here.

Use “implementation intentions,” as we covered above.

You can make implementation intentions even more effective by: (i) imagining you fail to achieve the goal, (ii) working out why you failed, then (iii) modifying your plan until you’re confident you’ll succeed. In this case, it’s negative thinking that’s most effective. You can read more in Rethinking Positive Thinking by Professor Gabriele Oettingen.

We know lots of people who swear by commitment devices, like Beeminder and stickK. Read more.

To go more in-depth on how to become more motivated, check out The Motivation Hacker, a short popular summary by Nick Winter, and The Procrastination Equation by Professor Piers Steel.

Productivity processes

Set up a system to track your tasks, especially small tasks like a simplified version of the Getting Things Done system (most people find the full system over the top, so you might want to first try something like Daniel Kestenholz’s Minimalist Productivity System). This helps you avoid forgetting things, and provides (some) peace of mind. Todoist is also a popular tool for managing tasks.

Do a five-minute review at the end of each day. You can put all kinds of other useful habits into this review, such as gratitude journaling, tracking your happiness, and thinking about what you learned each day. You can also use it to set your top priority for the next day: many people find it useful to focus on this first thing (a technique that’s been called “eating a frog“).

Each week, take an hour to review your key goals, and plan out the rest of the week. (And the same monthly and annually.) Here’s an example.

Share your to-do list. At the start of each day, try sending your to-do list to a friend or colleague. We find that just telling someone else is enough to give some motivation — even if there’s no formal accountability.

Batch your time. For example, try to have all your meetings in one or two days, then block out solid stretches of time for focused work; and clear your inbox once a week. Paul Graham discusses this in his essay, Maker’s schedule, manager’s schedule. This approach reduces the costs of task switching and attention residue. More detail on this can be found in our podcast episode with Cal Newport, or in his book Deep Work. Also, consider defining a fixed number of hours for work (for example, have a hard limit of stopping work by 6:00pm). Many people have found this makes them more productive during their work hours, while also reducing the chance of burning out and neglecting their social life. Read more. Toggl and HourStackare useful tools for tracking your time.

Be more focused by using the pomodoro technique. Whenever you need to work on a task, set a timer, and only focus on that task for 25 minutes. It’s hard to imagine a simpler technique, but many people find it helps them to overcome procrastination and be more focused, making a major difference to how much they can get done each day. Professor Barbara Oakley recommends it in her course, Learning how to learn. Another step would be to do this with someone else: tell each other what you’re each going to do in the 25-minute focus time, and then hold each other accountable at the end. Focusmate is a helpful platform for finding people to co-work with.

Build a regular daily routine, which you can use to complete tasks automatically — for example, always exercise first thing after lunch. Many people find having a good morning routine is especially important, because it gets you off to a good start.

Set up systems to take care of day-to-day tasks to free up your attention, like eating the same thing for breakfast every day.

Block social media. It’s designed to be addictive, so it can ruin your focus. Changing tasks a lot makes you less productive due to attention residue. For this reason, many people have found tools that block social media during work hours, or for a certain amount of time each day, to majorly boost their productivity. Consider: Rescue Time, or Freedom. Or reward yourself for focused work with apps like Forest.

Further reading on productivity

A huge amount has been written about all of these ideas. Hopefully, this gives you an idea of what’s out there and some ways to get started. When you’ve spent a few months incorporating some of these habits into your routines, move on to the next step.

Here are some systems and over-the-top reflections from highly productive people:

Deep Work by Cal Newport

Productivity by Sam Altman

Pmarca guide to personal productivity by Marc Andreessen

Seeking the productive life by Stephen Wolfram

How I am productive by Peter Hurford

Interviews with productive people in the effective altruism community by Lynette Bye

6. Improve your basic social skills

Social skills are useful for almost everything in life, and although there’s surprisingly little good advice on how to improve them, there are some really basic things that everyone can learn. Small habits, like how to make smalltalk and changing how you think about social situations, can make it much easier to make friends, get on with colleagues, and generally deal with people.

The most popular guide to learning basic social skills is probably How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie. It’s full of advice like “A person’s name is to that person, the sweetest, most important sound in any language.” We think the advice is a bit dated and simplified, and sometimes sounds a bit manipulative, but many people find it helpful. Here’s a summary of the book by Bryan Caplan that highlights the best ideas.

If you’re looking to develop more advanced social skills, then you might find The Charisma Myth by Olivia Fox Cabane useful. It makes at least some attempt to use the limited research that exists. Other people have found things like improv and Toastmasters helpful.

Finally, much comes down to practice, and getting comfortable talking to new people. So it’s useful to work on this area while also following the steps in the next section…

7. Surround yourself with great people

Everyone emphasizes the importance of networking for a successful career, and they’re right. Many jobs are found through connections, and some positions are never publicly advertised—they’re available only through referrals.

But for Christians, the value of connections goes far beyond job opportunities. Proverbs 13:20, “Walk with the wise and become wise, for a companion of fools suffers harm’ reminds us that the people we surround ourselves with can profoundly shape us. While it might be overstating things to say, “You become the average of the five people you spend the most time with,” there’s truth in the idea. Friends influence our sense of what’s normal, affect our emotions, and can teach us new skills or connect us with others.

Research even measures this influence. The book Connected by Christakis and Fowler reviews studies showing that when one friend becomes happy, you’re 15% more likely to be happy, and if a friend of a friend becomes happy, you’re 10% more likely to be happy. This reflects the impact of “iron sharpening iron” (Proverbs 27:17) in our own lives.

Connections are also a valuable source of wisdom and guidance. For instance, if you’re making decisions over a particular problem area or ministry, talking to someone already in that area can provide insights and encouragement. This applies not just to careers but to any area where we’re seeking to grow.

When starting new projects or making decisions, our network can be a vital support, as we are more likely to trust those we know well. For those focused on a positive impact, connections matter even more. If we’re passionate about causes like global health or animal welfare, for instance, we can share these passions within our circle, sparking a ripple effect that amplifies God’s work in the world.

In building a strong network, we’re not just helping ourselves; we’re creating a community that can stand together, encourage one another, and further God’s kingdom.

Practical tips on how to build connections

Networking sounds icky, but at its core, it’s simple: meet people you like, help them out, and build genuine friendships. If you meet lots of people and find small ways to be useful to them, then when you need a favour, you’ll have lots of people to turn to. However, it’s best just to help people with no expectation of reward — that’s what the best networkers do and there’s evidence that it’s what works best.9

You don’t have to meet people through networking conferences. The best way to meet people is through people you already know — just ask for an introduction and explain why you’d like to meet (here are some email scripts). Alternatively, you can meet people through common interests — things you actually enjoy doing.

When you meet a new person, a useful habit is the “five-minute favour.” Think of what you can do in just five minutes that would help this person, and do it. Two of the best five-minute favours are to make an introduction, or tell someone about a book or another resource. The right introduction can change someone’s life, and costs you almost nothing.

But it still takes effort to reach out to people. In the long term, it’s even better to develop habits that will let you build connections automatically. For instance, join a group that meets regularly, or live with people who have lots of visitors. Starting a side project can also work well — it gives you a good reason to meet people and work alongside them, building more meaningful connections.

Don’t forget that you want both depth and breadth in your connections — it’s useful to have a couple of allies who know you really well and can help you out in a tough spot, but it’s also useful to know people in many different areas so you can find diverse perspectives and opportunities — there’s evidence that being the ‘bridge’ between different groups is what’s most useful for getting jobs.

Draw up a list of your five most important allies, then make sure to stay in touch with them regularly. But also think about how to meet totally new types of people for breadth.

8. Apply scientific research into happiness

Although most advice about being happier isn’t based on anything much, the last few decades has seen the rise of “positive psychology” — the science of the causes of wellbeing.

Researchers in this field have developed practical, easy exercises to make you happier, and tested them with rigorous trials to see whether they really work. We think this is one of the best places to turn for self-help advice.

Partly, this research emphasises the importance of the basics — sleep, exercise, family and friends, and mental health. But they’ve made lots of other useful discoveries too.

Being happier is not only good in itself, but it can also make you more productive, a better advocate for social change, and less likely to burn out.

Below is a list of techniques recommended by Professor Martin Seligman, one of the founders of the field. Most of these are in his book, Flourish. Some of these techniques have been successfully replicated and multiple recent meta-studies have found statistically significant positive effects of all of these techniques.Test them out, and keep using them if they’re helpful.

Reflect on Your Happiness: At the end of each day, take a moment to assess your happiness. This practice cultivates self-awareness and helps you track your spiritual growth. Consider using a journal to document your feelings.

Practice Gratitude: Write down three things you are grateful for at the end of each day, and reflect on how God has blessed you through these moments. You might also consider expressing your gratitude in prayer.

Utilise Your Strengths: Take the VIA Character Strengths survey to identify your top strengths, and aim to use one of them each day. Recognizing and applying your unique gifts can deepen your sense of purpose.

Engage in Cognitive Behavioral Techniques: Learn basic principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Much of our unhappiness stems from unhelpful beliefs; by aligning our thoughts with God's truth, we can have our perspectives transformed.

Practice Mindfulness and Prayer: Mindfulness, often practiced through meditation, can enhance wellbeing. Consider dedicating 20 minutes each day to prayer or meditation, focusing on God’s presence and peace.

Perform Acts of Kindness: Make it a daily habit to do something kind, whether it’s donating to charity, complimenting a friend, or assisting a coworker. These acts not only bless others but also uplift your spirit.

Celebrate Others’ Successes: Practice active constructive responding by rejoicing in the achievements of others, and experiencing shared joy.

Craft a Meaningful Work Life: Reflect on your job and identify how you can incorporate more fulfilling aspects into your daily tasks. Finding deeper meaning in your work—perhaps by connecting with those you serve—can increase your satisfaction and impact.

By integrating these practices into your life, you can cultivate a deeper sense of happiness and purpose. Remember that joy is not just a personal pursuit but a reflection of God's love and grace in our lives.

9. Use these tips to save more money

We recommend aiming to save enough money that you could comfortably live for at least six months if you had no income, and ideally 12 months (depending on how long it would take you to find another job). Besides the security, it also gives you the flexibility to make big career changes and take risks. The standard advice is also to save about 15% of your income for retirement.

So how can you go about saving money?

Save automatically. Set up a direct debit from your main account to a savings account, so you never notice the money.

Focus on big wins. Rather than constantly scrimping (don’t buy that latte!), identify one or two areas of your budget you could cut that will have a big effect. Often cutting rent by moving somewhere smaller or sharing a house with someone else is the biggest thing.

But beware of swapping money for time. Suppose you could save $100 per month by moving somewhere with an hour longer commute. Instead, maybe you could spend that time working overtime, making you more likely to get promoted, or earning extra wages. You’d only need to earn an extra $5 an hour to break even with the more expensive rent.

Until you have six months’ runway, cut your donations back to 1%.

Bear in mind that it might be more effective to focus on earning more rather than spending less, especially through negotiating your salary.

Once you’re saving 15% and have at least 6–12 months’ runway, move on to the next step.

10. Learn how to learn

Another skill that will help you in every job is learning how to learn.

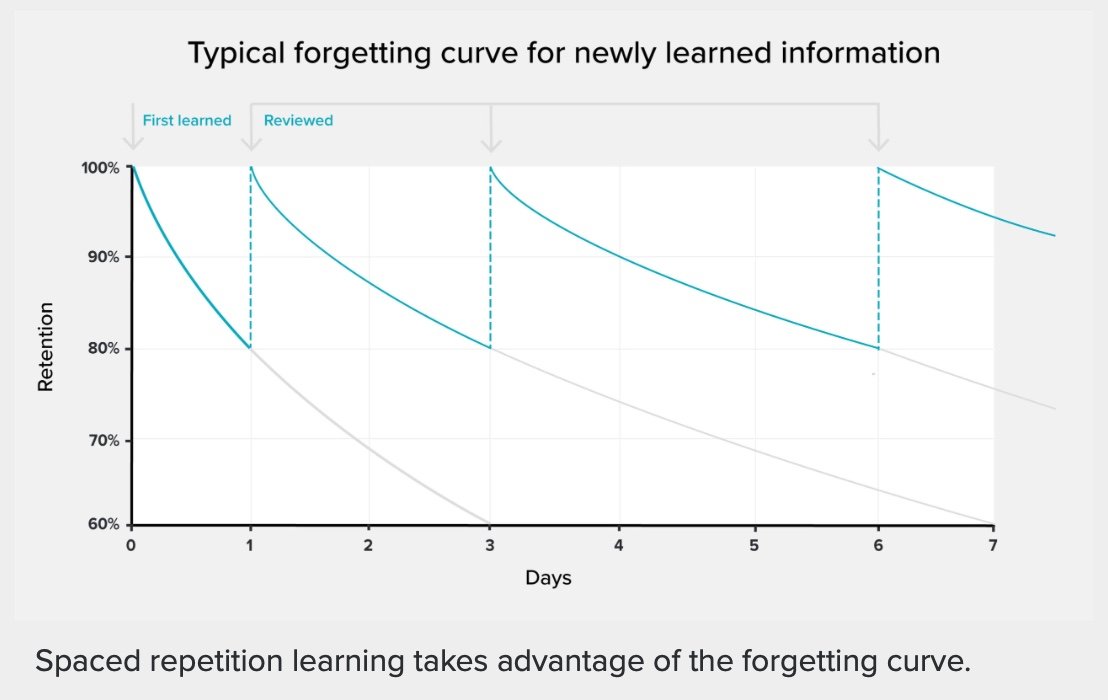

Perhaps surprisingly, you can become much faster at learning. One example is spaced repetition. If you’re trying to memorise something, like a word in a foreign language, research shows that there’s an optimal frequency to review the word. If you use this frequency, you’ll be able to memorise it much faster. There are now tools that will do this for you, like Anki for making your own flashcards. Take a look at this essay on using Anki.

There are lots more techniques. Our top recommendation in this area is the Learning How to Learn course on Coursera by Professor Barbara Oakley, which is now the most viewed online course of all time. You can also read the book it’s based on, A Mind for Numbers.

If you’re interested in learning about a specific topic in detail, or forming a new opinion in an area that’s important, it could be helpful to try learning by writing.

Finally, Peak by Professor K. Anders Ericsson is a fascinating (if polemical) book about the importance of practice in developing expertise, and how to practice most effectively. In brief, you need to have:

Specific goals for your practice, focused on improving your weaknesses.

Rapid feedback on how well you’re performing.

Intense focus on the task.

A good coach or teacher.

Many people have spent thousands of hours driving, but they’re not expert drivers. This is because they don’t practice with all these ingredients, and their skill quickly tops out. This is the same for many people in many jobs.

Deliberate Performance is a great paper by Fadde and Klein about how to turn any activity into practice that improves your skills. See a summary.

When you’ve learned the basics, go on to learning more narrowly applicable skills, as we cover in the next two steps.

11. Be strategic about how to perform better in your job

How can you perform better in your job? As we covered earlier, being good at your job brings all kinds of other benefits:

You’ll have better achievements and connections, boosting your career capital.

You’ll gain a sense of mastery, making you more satisfied.

You’ll have more positive impact.

Working harder helps — if you can go 10% beyond what everyone else is doing, that’s often all that’s needed to stand out. But it’s better to work smarter rather than harder.

One key question to ask is: “What is really required for advancement in this position?” It’s easy to get distracted, but there are often only a few things that really matter. For a salesperson, it’s the revenue they bring in. For an academic, it’s how many good papers they publish.

Talk to people who have succeeded in the area, and try to identify what this key thing is. Don’t just trust what they say; work out what they actually did. Then, using the material in the earlier section on learning how to learn, figure out how to master it. Try to cut back on everything else.

To learn more, we recommend Cal Newport’s work:

The Top Performer online course. You can see some of the key ideas in this series of posts by the course co-creator Scott Young:

12. Use research into decision-making to think better

Another example of a skill that’s useful in every job, but often not explicitly taught, is clear thinking. Research suggests that intelligence and rationality are distinct (perhaps that’s why smart people make so many dumb decisions), but fortunately, rationality is easier to train.16

Clear thinking is also especially important if you want to make the world a better place. As we show in the rest of this guide, having a big social impact requires making lots of tough decisions and overcoming our natural biases — and it means doing that in areas where there are no clear answers, and our judgement is all we have to rely on.

So, how can you become more rational?

Broadly, it’s about having the right mindset, building the right habits of thinking, and practice.

Some of the best research about learning to think better is Philip Tetlock’s research on forecasting. He had people make predictions about difficult-to-predict things — like who would win the next election, or whether Russia would declare war on Ukraine — and measured who performed best. He then identified the traits of the best forecasters, and used this to develop a forecasting training programme. Finally, he tested that programme and found some good evidence that it really does help people make better predictions!

Drawing from this research, 80,000 Hours have written a separate article about how to improve your judgement, which summarises the mindset and techniques of good forecasters. It also explains how you can test your skills by doing calibration training or through making your own forecasts.

What else can help with learning to think better more broadly?

On developing the right mindset, we’d recommend the book Scout Mindset by Julia Galef.

Partly it involves building up better habits of thinking. Decades of research have shown that we often make bad decisions due to cognitive biases.

Being aware of these biases is unfortunately not enough to overcome them, but it can motivate us to improve our thinking, and research has found there are habits of thinking you can instil that make you more resistant to these biases.

For instance, several studies of decision-making found that “whether or not” decisions — those that only consider one option — were much less likely to be judged successful than those where several options were simultaneously compared. This suggests it may be helpful to develop a simple habit of always considering at least three options when you make decisions. This and much more advice is covered in Decisive by Chip and Dan Heath.

To accurately understand the world or predict the future, it’s important to update your opinions in the right way (i.e., in line with Bayes’ theorem) each time you encounter a new piece of evidence. This is such an important idea that 80,000 Hours made a podcast episode all about it: How much should you change your beliefs based on new evidence? Dr Spencer Greenberg on the scientific approach to solving difficult everyday questions.

Finally, you can become better at thinking by building up your toolkit of concepts and mental models. This means understanding the big ideas in every field. Former 80,000 Hours staff member, Peter McIntyre, created a list of 52 key concepts, which you can sign up to learn over a year via a weekly email.

It’s particularly important to understand basic statistics and decision analysis. A great book about taking a rational approach to messy problems is How to Measure Anything, by Douglas Hubbard.

13. Teach yourself these useful work skills

Having set up the basics, learned the skills that make you more effective at everything, and thought about how to best perform in your job, it’s time to turn your attention to classic work skills, like management and marketing.

The best way to improve these skills is to apply them in the course of your job, while getting feedback from someone more experienced.

So rather than self-study, try to incorporate new skills into your day-to-day work, or start a side project. For instance, if you want to learn web design, then volunteer to design a page for a group you’re involved with. Doing projects is also much more motivating than trying to learn in the abstract.

However, self-study is also easier than ever before thanks to the huge growth in cheap online courses, like Udacity, Coursera, and EdX.

Which skills are best to learn?

80,000 Hours did an analysis of which transferable work skills are most useful in the most desirable jobs, finding broadly that the best are:

Analysis — including decision making, critical thinking and problem solving.

Learning new skills and information.

Social skills — including spoken communication, active listening, social perceptiveness, and persuasion.

Management — including time management, monitoring performance, monitoring personnel, and coordinating people.

We could broadly classify these as “leadership” skills. And they still look to be among the most valuable skills in the age of GPT.

We’ve covered many ways to improve these skills already in the sections above on good thinking, learning how to learn, and improving your social skills.

The problem with leadership skills is that, while you can make some improvements, after learning the basics your rate of improvement tends to slow up quite a bit.

Consider the contrast with computer programming: you can go from having zero knowledge to having useful abilities in a year or two of practice, and advanced expertise beyond that.

So what to do? Our suggestion is to take any concrete ways you can see to noticeably improve the leadership skills listed, and then focus on concretely useful but faster-to-learn skills after that, such as technical and quantitative skills, or other specialist skills that seem especially useful to your career plans.

You also need to consider your personal fit. Some skills will be faster for you to learn than others, and this will make your efforts more effective. And you need to consider which skills will be most useful in the options you want to take in the future.

In other words, you want to look for the skills that have the best combination of: (i) future value to your career, and (ii) being quick for you to learn.

14. Take these steps to master a field and make creative contributions

After you’ve taken the low-hanging fruit from the steps above, and explored different areas, one end game to consider is becoming a leader in a valuable skill set or global problem. This is where you gain the deep satisfaction of mastery, and can make a big impact on a field. However, while the previous points can be covered in years, becoming an expert usually takes decades.

So, how can you become an expert? This is a subject of huge debate.

A common belief is that in every area, some people are naturals, and can attain mastery with ease.

The most famous researcher in the study of expert performance, K. Anders Ericsson, however, mostly debunked this idea. For any area where large differences in skill exist, the highest-performing people have all done a huge amount of focused practice, usually with top mentors. Child prodigies, like Mozart, got ahead by practicing more and from a younger age.

However, there is still debate about whether practice is the main thing you need, or whether talent is also important. Given that there’s not yet a consensus, we think the most reasonable position is to assume that both matter.

So this means that to become an expert you need four things:

Talent for the area.

The right training techniques and mentorship.

Five to 30 years of focused practice.

Luck.

How much practice is required depends on the area. There’s evidence that it’s most important in well-established, predictable domains, like running. In newer, more fluid areas, you can get to the forefront faster.

So how should you choose where to focus?

First, if you’re going to put in (maybe) decades of work, you’ll want to pick an area or skill that’s valuable. See our material on which global problems are most important, how to find a job you’ll love, and high-impact career paths.

Second, you’ll want to choose an area where you have a reasonable shot at attaining expertise. One shortcut here is to focus on a field that’s new and neglected, since then it’ll be much easier to get to the forefront. For instance, we think GiveWell established themselves as experts on charity evaluation in about five years, despite having little background in the area.

Beyond that, it’s hard to predict who’s going to perform best ahead of time. So while it’s possible to narrow down by, for instance, asking experts to assess your potential, ultimately it’s important to try lots of areas.

Here’s an overall process you could roughly work through for choosing what to focus on:

Consider a lot of options. Explore and try them out in small ways.

Narrow these options down based on: (i) where you think you’d have the best chances of success, (ii) what you think you’d enjoy, and (iii) what seems most valuable to master.

To assess your chances of success, you can consider: (i) where you’re improving fastest, (ii) expert assessment of your potential, (iii) objective predictors of success (e.g. getting into a top PhD programme is predictor of success in research), and (iv) what’s most motivating you — since staying motivated for many years is necessary for success. Apply the material on making better predictions that we covered above.

Consider committing for a couple of years, and then reassess. Use this as an opportunity to apply the research about how to learn effectively that we covered above.

If that goes well, consider making a bigger commitment to the skill or area. Be prepared for years of hard work, but bear in mind that your interest in the area will probably grow as you gain mastery, and you start to use your skills to help others.

To learn more about how to develop expertise, we’d recommend Peak by K. Anders Ericsson (though bear in mind he’s the strongest supporter of practice over talent). We’d also recommend Grit by Angela Duckworth, which is about how to develop your passion and perseverance.

Another key way experts contribute is by coming up with new solutions that no one has thought about before. Unfortunately, we’re not aware of much good advice on how to be more innovative, but one recommendation is Originals by Professor Adam Grant.

Once you become an expert, what then? Use your skills to solve the world’s most pressing problems. Do what contributes.

You can learn more about what each problem most needs in our problem profiles.

How to have impact

Even if you find yourself in a job that doesn't feel ideal right now, there is still much you can do to cultivate joy, enhance your productivity, and make a positive impact in the world around you.

As Richard Hamming wisely noted, knowledge and productivity are like compound interest: two individuals of similar ability can produce vastly different outcomes based on their dedication. If one person puts in just 10% more effort, they can significantly outproduce their counterpart. The more you invest in learning, the more opportunities you will uncover to serve others and fulfill God’s purpose for your life.

When you apply principles of productivity and learn how to learn effectively, you will be able to grasp new skills and knowledge more quickly. Surrounding yourself with supportive, faith-filled friends also plays a crucial role in your journey, encouraging you in all aspects of life.

Over time, through prayer, reflection, and consistent effort, you can learn to have a positive impact and build your career in a way that glorifies God and benefits those around you.

So, choose one of these areas to focus on today and take a step forward.

Summing Up

Understand what success and impact means in light of your faith and values.

Build relationships with fellow believers who can support and encourage your journey.

Embrace continuous growth in knowledge and spiritual maturity.

Be open to taking risks.

Need help discerning your career? Sign up for our free one-on-one impact mentorship here.

To read more about it click here.

Do you have any career uncertainties? Click here to read our article on three big career uncertainties you can trust God with.