Which Jobs Help People The Most?

Written October 25 2024

Est. 15-20 minute read

This article draws heavily from 80,000 Hours (see their up-to-date entry here).

Many people think of Superman as a hero. But what if he’s actually an example of underutilised talent in all of fiction? His life was spent fighting crime one case at a time, which may have limited the good he could have done. Imagine if, instead, he’d used his abilities to deliver vaccines at superspeed, eradicating many diseases and saving millions of lives. This bigger vision could have led to a far greater impact—a calling to serve the world in a new way.

In the same way, many of us feel may want to “make a difference” through our careers. We often think of paths like medicine or teaching as the clearest way to serve. But sometimes, we limit the unique gifts God has given us by focusing on what feels familiar or traditionally impactful. Like Superman fighting one crime at a time, these paths can be important yet may not fully use the specific talents we’ve been blessed with.

Think of Karl Landsteiner, a Nobel Prize winner who discovered blood groups, making lifesaving transfusions possible for millions. By using his skills in research and discovery, he achieved a life-saving impact that would have taken countless doctors to achieve individually.

Below we’ll introduce five ways you could use your career to help tackle the social problems you want to help work on: earning to give, communicating ideas, research, government and policy, and organisation-building. You can think of each of these as a valuable skill set that can help you make a bigger contribution to solving global problems.

Approach 1: Earning to give

Would Elton John have done more good if he’d worked at a small nonprofit? We don’t normally think of becoming a rockstar as a path to doing good, but (quite apart from the value of his music!) Elton John has saved the lives of thousands of people by reducing the spread of HIV/AIDs.

Photo by Ernst Vikne

So here’s one way of doing more good that’s not normally put on the table: earning to give.

We often meet people who are interested in taking a higher-earning job, like software engineering, but are worried they won’t make a difference if they do. Part of the reason is that we don’t usually think of earning more money as a path for people who want to do good. However, there are many effective organisations that have no problem finding enthusiastic staff, but don’t have the funds to hire. People who are a good fit for a higher-earning option can donate to these organisations, making a large indirect contribution.

We define “earning to give” as working in a job with a neutral or positive direct impact, which pays more than what someone would have done otherwise, and while donating a large fraction of the extra earnings (typically 20–50% of the total salary) to organisations they think are highly effective.

Earning to give is not just for people who want to work in the highest-paying industries. Anyone who aims to earn more in order to give more is on this path. But if you’re a good fit for a higher-earning path, it could be one of your higher-impact options.

Consider the story of Grayden, which is a powerful example of how high-earning careers can drive impactful change through strategic philanthropy.

Starting his career in strategy consulting, Grayden encountered the unique needs of nonprofits and realised that what many needed most was funding, not just more people. This insight inspired him to pursue a high-earning path in consulting and, later, investing, allowing him to use his income to support effective charities. As a Carve-Out Investor, he doubled his earnings potential and began donating a substantial portion of his income, contributing over £250,000 to causes like global health, development, and animal welfare by 2017.

By following this path, Grayden likely achieved more impact than he might have working directly in a nonprofit. With his donations, he supports multiple nonprofit salaries while still living comfortably.

His journey highlights the potential of “earning to give,” all while keeping a faith-driven focus on living sacrificially and purposefully.

Making this much difference is possible because (as we saw earlier) we live in a world with huge income inequality — it’s possible to earn several times as much as a teacher or nonprofit worker, and vastly more than the world’s poorest people. At the same time, hardly anyone donates more than a few percent of their income, so if you are willing to do so, you can have an amazing impact in a very wide range of jobs.

It is known that that any college graduate in a developed country can have a major impact by giving 10% of their income to an effective charity. The average graduate earns $77,000 per year over their life, and 10% of that could save about 40 lives if given to Against Malaria Foundation, for example.

If you could just earn 10% more, and donate the extra, then that’s twice as much impact again. And if you think there are better organisations to fund than Against Malaria Foundation — perhaps working on different problems, or doing research, or communicating important ideas — the impact is even higher.

Since the introduction of the concept of “earning to give” in 2011, hundreds of people have taken it up and stuck with it. Some give around 30% of their income, and a few even give more than 50%. Collectively, they’ll donate tens of millions of dollars to high-impact charities in the coming years. In doing so, they are funding passionate people who want to contribute directly, but who otherwise wouldn’t have the resources to do so.

Should you earn to give?

80,000 Hours explores earning to give and it has been one of their most memorable and controversial ideas, attracting media coverage in the BBC, Washington Post, Daily Mail, and many other outlets.

For this reason, many people think it’s their top recommendation. But it’s not.

Like 80,000 Hours, we see earning to give mostly as a baseline. It’s a path that many could pursue and do a lot of good — on the scale of saving 100 lives or more, as we just argued.

But we think that most of our readers can have an even greater impact again by pursuing one of the other approaches below. Overall, for people we speak to one-on-one, we only think about 10% should earn to give.

When is earning to give especially promising?

You’re a good fit for a higher earning option, like Grayden in finance, and you’re not a good fit for other impactful options. (Definitely don’t work in finance if you’d hate it!)

There’s a particular job you really want to do for other reasons where you think you can make significant donations. For instance, you might be someone who’s always wanted to be a doctor, or you might need a higher-earning job to support your family.

You think a higher-earning option will be good for building skills (for use in more direct work later on), and earning to give could help you to stay engaged with social impact while you do so. For example, working at a tech startup can help you learn organisation-building skills that are useful when running nonprofits.

You’re very uncertain about which problems are most pressing. Earning to give provides flexibility because you can easily change where you donate, or even save the money and give later. (Though money isn’t the only thing that’s transferable! Many skills — including those we cover below — can easily be transferred across problem areas.)

You want to contribute to an area that is particularly funding-constrained rather than primarily talent constrained.

Common objections to earning to give

Don’t many high-earning jobs cause harm?

As Christians, we are called to be stewards of our resources and to seek the good of others in all our actions. While the idea of "earning to give"—choosing high-paying careers to donate generously—is admirable, we must exercise caution in the types of jobs we pursue.

We believe that taking a job that inflicts harm, even with the intention of donating the earnings to worthy causes, is generally not in line with our faith. Scripture teaches us to love our neighbors and to do good, so we should strive for careers that have a positive impact on all of those around us.

Many individuals in the "earning to give" community find fulfilling work in areas such as technology, healthcare, and consulting, where their contributions can benefit society. However, we must recognize that some high-earning roles can lead to moral dilemmas. A notable example is Sam Bankman-Fried, who initially portrayed himself as someone dedicated to making a positive impact through his cryptocurrency exchange. Unfortunately, he faced serious charges of fraud, which serve as a reminder of the potential pitfalls of pursuing wealth without ethical considerations.

Ultimately, while earning a substantial income can enable us to support the work of God's kingdom, we must always weigh our career choices against the teachings of Christ. Engaging in work that harms others for the sake of profit or donation is rarely justifiable. Our calling is to embody Christ’s love in all aspects of our lives, including our professional choices, striving to uplift others through our actions and decisions.

Can people actually stick with it?

Won’t people earning to give end up being influenced by their peers to spend the money on luxuries rather than donating? When 80,000 Hours first introduced the idea, they had this initial concern but it hasn’t happened as often as you might think. Hundreds of people are pursuing earning to give, and while some have left because they thought they could do more good elsewhere, surprisingly few (that they know of) have simply given up their plans to donate. In part, this is because many people pursuing earning to give made public pledges of their intentions to donate, often through Giving What We Can. The existence of a community that earns to give also makes it much easier to stick with today.

But if you try to earn vast sums of money, there’s a much more substantial risk: that power corrupts. For this reason, we’re more concerned about people who try to earn as much as possible, to the exclusion of all else. We’d suggest publicly precommitting to making donations. And, if you do end up with a lot of money, you should set up safeguards to help make sure you use the money responsibly — such as a board, formal governance structures, and advisors who can keep you in check. Read more about the risk of being corrupted by a higher-earning career.

What if I wouldn’t be motivated doing a high-earning job?

In that case, don’t do it. We only recommend earning to give if it’s a good fit. Just bear in mind, that you can become interested in more jobs than you might think.

Approach 2: Communicating ideas

Consider the following options:

Earn to give yourself.

Persuade two friends to earn to give.

The second path does more good — in fact, probably about twice as much. This illustrates the power of communication careers.

Many of the highest-impact people in history have been communicators and advocates of one kind or another — people who spread important ideas and solutions to pressing problems.

Take Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat to a white man on a bus, sparking a protest which led to a Supreme Court ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional. Parks was a seamstress in her day job, but in her spare time she was very involved with the civil rights movement. After she was arrested, she and the NAACP worked hard and worked strategically, staying up all night creating thousands of fliers to launch a total boycott of buses in a city of 40,000 African Americans, while simultaneously pushing forward with legal action. This led to major progress for civil rights.

Many of the highest-impact people in history were communicators and advocates of some kind, and you can become an advocate in any job. Rosa Parks worked as a housekeeper and seamstress before making a stand for civil rights.

There are also many examples you don’t hear about, like Viktor Zhdanov, who was arguably one of the highest-impact people of the 20th century.

In the 20th century, smallpox killed around 400 million people — far more than died in all the century’s wars and political famines. Credit for the elimination often goes to D.A. Henderson, who was in charge of the World Health Organization’s smallpox elimination programme. However, the programme already existed before Henderson was brought on board. In fact, he initially turned down the job. The programme would probably have eventually succeeded even if Henderson hadn’t accepted the position.

Zhdanov single-handedly lobbied the WHO to start the elimination campaign in the first place. Without his involvement, it would not have happened until much later, and possibly not at all.

So why has communicating important ideas sometimes been so effective?

First, ideas can spread quickly, so communicating them is a way for a small group of people to have a large effect on a problem. A small team can launch a social movement, lobby a government, start a campaign that influences public opinion, or just persuade their friends to take up a cause. In each case, they can have a lasting impact on the problem that goes far beyond what they could achieve directly.

Second, spreading important ideas in a careful, strategic way is neglected. This is because there’s usually no commercial incentive to spread socially important ideas. Instead, advocacy is mainly pursued by people willing to dedicate their careers to making the world a better place. Moreover, the ideas that are most impactful to spread are those that aren’t yet widely accepted. Standing up to the status quo is uncomfortable, and it can take decades for opinion to shift. This means there’s also little personal incentive to stand up for them.

Communicating ideas is also an area where the most successful efforts do farmore than the typical efforts. The most successful advocates influence millions of people, while others might struggle to persuade more than a few friends. This means if you’re an exceptionally good fit for communicating ideas, it’s often the best thing you can do, and you’re likely to achieve far more by doing it yourself than you could by funding someone to engage in communication or advocacy on your behalf.

Communication careers can be pursued as a full-time job (such as many jobs in the media), as part of a wider role (like an academic who does science communication), or alongside almost any job (like Rosa Parks).

Communication careers are defined by their focus on spreading ideas on a big scale, but it’s also possible to have a similar impact on a more person-to-person level as a community builder.

Approach 3: Research

People often pan academics as Ivory Tower intellectuals whose writing has no impact. And we agree there are many problems with academia that mean researchers achieve less than they could. However, we still think research is often high impact, both within academia and outside it.

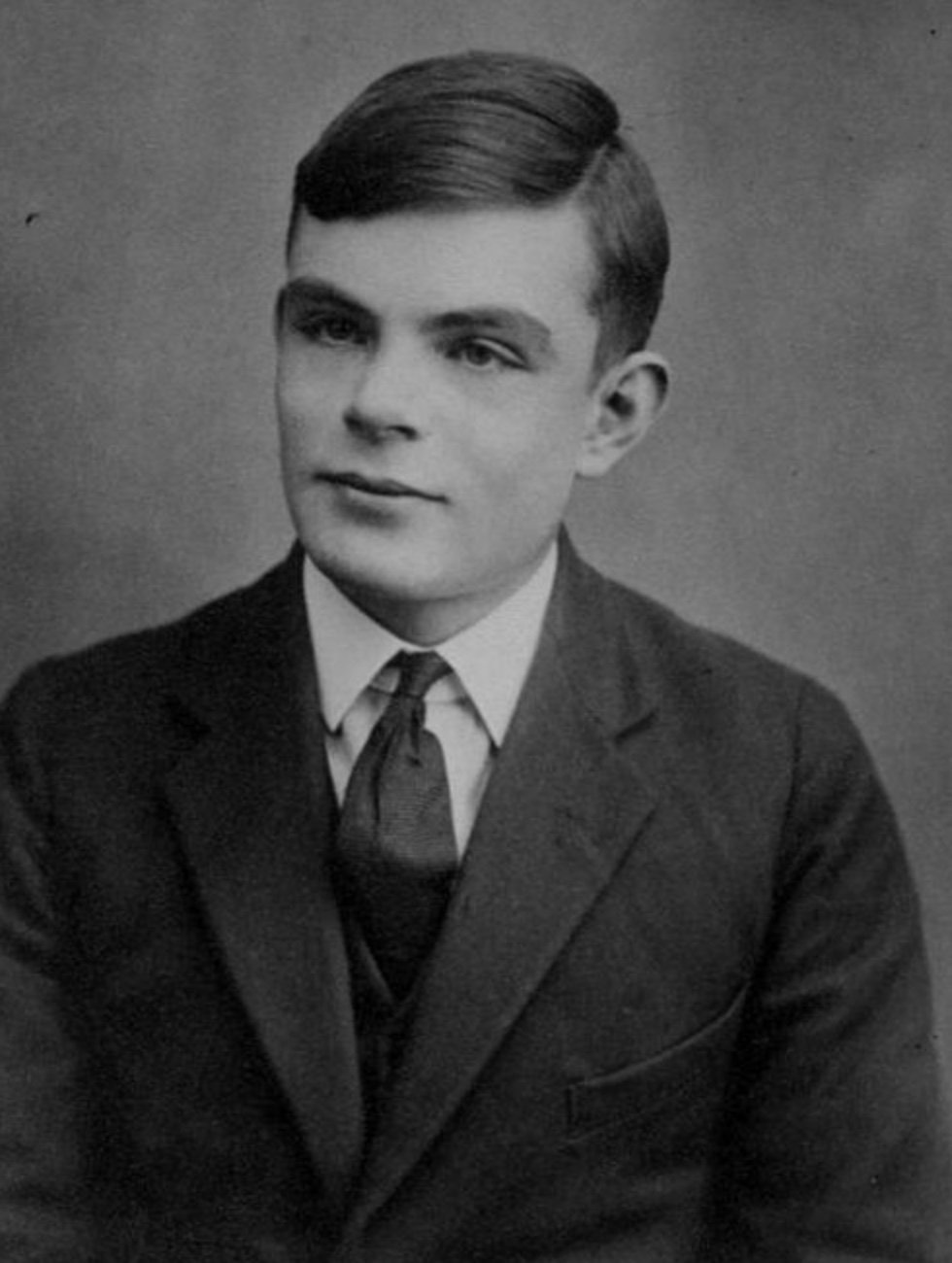

Along with communicators, many of the highest-impact people in history have been researchers. Consider Alan Turing. He was a mathematician who developed code-breaking machines that allowed the Allies to be far more effective against Nazi U-boats in World War II. Some historians estimate this enabled D-Day to happen a year earlier than it would have otherwise. Since World War II resulted in 10 million deaths per year, Turing may have saved about 10 million lives.

And he invented the computer.

Turing’s example shows that research can be both theoretical and high impact. Much of his work concerned the abstract mathematics of computing, which wasn’t initially practically relevant, but became important over time.

Of course, not everyone will be an Alan Turing, and not every discovery gets adopted. Nevertheless, we think that in some cases, research can be one of the best ways to have an impact. Why?

First, when new ideas are discovered, they can be spread incredibly cheaply, so it’s a way that a single career can change a field. Moreover, new ideas accumulate over time, so research contributes to a significant fraction of long-run progress.

However, only a relatively small fraction of people are engaged in research. Only 0.1% of the population are academics,6 and the proportion was much smaller throughout history. If a small number of people account for a large fraction of progress, then on average each person’s efforts are significant.

Second, because there’s little commercial incentive to do research relative to its importance, if you do care more about social impact than profit, then it’s a good opportunity to have an edge. Most researchers don’t get rich, even if their discoveries are extremely valuable. Turing made no money from the discovery of the computer, whereas today it’s a multibillion-dollar industry. This is because the benefits of research come a long time in the future, and can’t usually be protected by patents.

In fact, the more fundamental the research, the harder it is to commercialise, so, all else equal, we’d expect fundamental research to be more neglected than applied research, and therefore higher impact. On the other hand, applied issues can be more urgent — breakthroughs like the microscope can let us make fundamental breakthroughs faster — so it’s hard to say whether applied or fundamental research has a higher impact on average.

So in theory, research can be very high impact. But does research actually help with the most pressing problems facing the world today?

We think it does. When you look at the problems we’re most concerned about — like preventing future pandemics or climate change — many are mainly constrained by a need for additional research.

For example, research could help us develop ways to decrease the time it takes to go from a novel pathogen to a safe, widely distributed vaccine. As another example, technical machine learning research could help us build safeguards into AI systems to prevent dangerous behaviour. For more ideas, and to get a sense of what you might be able to work on in different fields, see this list of potentially high-impact research questions, organised by discipline.

Like communicating ideas, research is especially promising when you’re a very good fit, because the best researchers achieve much more than the median. Most papers only have one citation, whereas the top 0.1% of papers have over 1,000 citations. And when 80,000 Hours did a case study on biomedical research, remarks like this were typical:

One good person can cover the ground of five, and I’m not exaggerating.

If you might be a top 20% researcher in a topic that’s relevant to a pressing problem area, then it’s likely to be one of your most impactful options. And if you might be exceptional in an academic field (maybe, top few percent), even if you can’t see now how it’ll be useful, that’s an option you should probably seriously consider.

Don’t forget supporting positions

Becoming an academic administrator doesn’t sound like a high-impact career, but that’s exactly why it is. Research requires administrators, managers, grantmakers, and communicators to make progress. Many of these roles require very capable people who understand the research, but because they’re not glamorous or highly paid, it can be hard to attract the right people. For this reason, if a role like this is a good fit for you, then it can be promising. What ultimately matters is not who does the research, but that it gets done.

A hero of ours is Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh. He studied for a PhD in comparative genomics, but ultimately decided to pursue academic project management. He became a manager at the Future of Humanity Institute, which undertakes neglected research into emerging existential risks, like risks from AI and engineered pandemics. He did a huge amount of work behind the scenes to keep things running as funding rapidly grew. When there was an opportunity to start a new research group in Cambridge, he used what he’d learned to lead efforts there too — at one point managing both groups. The field would have moved much more slowly without his management.

If you’re interested in positions like these, the best path is usually to pursue a PhD, pick a field, then apply to research groups. If you want to enable great research, you need a combination of familiarity with the field and operations skills. Learn more about research management careers.

See a full guide to learning to do high-impact research, both within and outside academia.

Approach 4: Government and policy

When we think of careers that “do good,” we might not first think of becoming an unknown government bureaucrat. But senior government officials often oversee budgets of tens or even hundreds of millions. If you could enable those budgets to be spent just a couple of percent more effectively, that would be worth millions of extra dollars spent on those programmes. And more broadly, the scale of the influence in government positions can be enormous.

For instance, Suzy Deuster wanted to become a public defender to ensure disadvantaged people have good legal defence. She realised that in that role she might improve criminal justice for perhaps hundreds of people over her career, but by changing policy she might improve the justice system for thousands or even millions. Even if the impact per person is smaller, the numbers involved give her the chance of making a greater impact. She was able to use her legal background to enter government, and now works in the Executive Office of the President of the US on criminal justice reform, and from there she can explore other areas of policy in the future.

Government is often crucial in addressing many of the issues we most recommend people work on, because they are the only institutions that create and enforce laws and regulation.

For example, only governments can do something like ban battery cages for egg-laying hens.

They can also act to solve coordination problems that are difficult for individual actors to tackle. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, contact tracing was essential to slowing its spread, but it wasn’t in any individual’s self-interest to participate. Governments stepped in to provide contact tracing services, benefiting society as a whole.

Positions in policy require a wide range of skill types, so there should be some high-impact options for nearly everyone.

See a full guide to learning how to have an impact in policy.

Approach 5: Building organisations

When most people think of careers that “do good,” the first thing they think of is working at a charity.

The thing is, lots of jobs at charities just aren’t that impactful.

Some charities focus on programmes that don’t work, like Scared Straight, which actually caused kids to commit more crimes. Others focus on ways of helping that don’t have much leverage, like Superman fighting criminals one-by-one, or Dr Landsteiner focusing on performing surgeries rather than doing the work to discover blood groups.

Another problem is that many people want to work at organisations that are more constrained by funding than by the number of people enthusiastic to work there. This means if you don’t take the job, it would be easy to find someone else who’s almost as good. Think of a lawyer who volunteers at a soup kitchen. It may be motivating for them, but it’s hardly the most effective thing they could do. Donating one or two hours of salary could pay for several other people to do the work instead. Or they could do pro bono legal work, and contribute in a way that makes use of their valuable skills.

However, there are plenty of other situations when working for a nonprofit is the most effective thing to do.

Nonprofits can tackle issues that other organisations can’t. They can carry out research that doesn’t earn academic prestige, or do political advocacy on behalf of disempowered groups such as animals or future generations, or provide services that would never be profitable within the market.

And there are lots of nonprofits doing great work that really need more people to help build and scale them up. There are also lots of niches that aren’t being filled, where we need new nonprofits to be set up to tackle them.

More broadly, helping to build an organisation can be a route to making a big contribution, because organisations allow large groups of people to coordinate, and therefore achieve a bigger impact than they could individually. Moreover, if you help build or start an effective organisation, it can continue to have an impact even after you leave.

And if you can help make an already existing and impactful organisation somewhat more effective, that can also be a route to a big impact.

Clare joined Lead Exposure Elimination Project (LEEP) as its third staff member. She thought that joining LEEP would help build her career capital — especially her skills and connections — and, more importantly, that lead exposure in low- and middle-income countries is an important, solvable, and highly neglected problem. Since joining, Clare has developed LEEP’s programmes and managed the team implementing them, as well as led the hiring for crucial new staff. LEEP has since started working with governments and industry in 16 countries, and has successfully advocated for the government in Malawi to monitor levels of lead in paints.

These organisations don’t even need to be nonprofits — some social impact projects are better structured as businesses, and could also include think tanks, research groups, advocacy groups, and so on.

For instance, Send Wave enables African migrant workers to transfer money to their families through a mobile app for fees of 3%, rather than 10% fees with Western Union. So for every $1 of revenue they make, they make some of the poorest people in the world several dollars richer. Within three years, they’d already had an impact equivalent to donating millions of dollars, and they’ve grown even more since then. The total size of the market is hundreds of billions of dollars — several times larger than all foreign aid spending. If they can continue to slightly accelerate the rollout of cheaper ways to transfer money, it’ll have a big impact.

Organisation-building careers are a good fit for people who can develop skills in areas like operations, people management, fundraising, administration, software systems, and finance.

Pursuing this path usually means first focusing on building some of these skills (which can be done at any competent organisation), and then later on using them to contribute to the organisations you think are most impactful.

To find impactful organisations, think about which problems you think are most pressing, and then try to identify the best organisations addressing those problems. Finally, try to identify those that have a pressing need for your skills and a role that might be a great fit for you.

See a full guide to learning how to build high-impact organisations.

More ideas for impactful careers

These categories aren’t intended to be comprehensive. There are lots of impactful options that don’t naturally fit into them.

For example, experts in information security are sorely needed by organisations working to prevent AI-related and biological catastrophes. There aren’t very many trained information security experts to begin with, and only a few are trying to use their careers to solve these urgent problems.

To see a much longer list of ideas (which still isn’t exhaustive), check out our best Christian jobs guide.

Which is the right approach for you?

We've seen that by thinking broadly about our calling—considering options like earning to give, sharing ideas, conducting research, influencing government and policy, and building impactful organizations—there are many ways to address pressing problems in a way that honors God.

If you want to choose between these paths, how might you approach it?

As you seek to discern your path, remember this important principle: those who are particularly effective in a field often have an outsized impact. A landmark study on expert performance found that a small percentage of people are responsible for the majority of progress. The top 10% of contributors are often responsible for around 50% of a field’s productivity, while the most prolific contributor can be 100 times more productive than the least. This principle is similar to the parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14-30), which teaches us to use what God has given us for His glory.

The right path for you will be one that you enjoy, one that motivates you, and one where your skills can flourish in service to God’s kingdom. Sometimes, people feel tempted to take on roles they dislike simply because they think it will lead to more impact. But that approach often leads to burnout, and it could even discourage others. God calls us to serve with joy and wholeheartedness (Colossians 3:23-24), so it’s best to seek a role that aligns with this.

It’s normal to feel unsure, especially at the start of your career. Finding the right path often takes time, and God’s purpose for our lives often unfolds gradually. Early on, it’s okay to have a general sense of direction and allow it to become clearer over time.

While finding your fit is essential, it’s also important not to narrow down too soon. People can often become more interested in new work than they first realize. So, be open to God’s leading, giving yourself room to explore different approaches, then focusing on the areas where He seems to be blessing your efforts.

Conclusion: in which job can you help the most?

There are many ways to serve others in our careers, often beyond what we typically think. Elton John began as a singer and went on to save thousands of lives through his generosity and giving. Rosa Parks was a seamstress, yet her courage and advocacy helped ignite the civil rights movement in America. Alan Turing, a mathematician, played a critical role in ending World War II through his research, paving the way for modern computing.

While not all of us are called to be famous musicians or groundbreaking inventors, each of us has a unique calling and gifts that God can use. Even on a modest salary, anyone can make a remarkable impact through generosity, potentially even saving lives. Proverbs 11:24 reminds us that “the one who gives freely grows richer.” Beyond financial giving, we can also make a difference by sharing important ideas, conducting meaningful research, working in government or policy, or helping build organizations that serve others.

By broadening our view of what a “calling” can look like, we often find paths that fit us better and allow us to serve in ways that align with our God-given gifts. So even if you don’t feel led to be a doctor or teacher, remember that there are many ways to glorify God and serve others through your career. No matter what path you’re on, trust that He can use you to make a difference for His kingdom and His people.

Summing up

Careers across fields like research, policy, and advocacy can be impactful ways to serve others.

Building or supporting organisations can help scale positive, lasting change.

“Earning to give” enables people to serve by directing their income toward causes that reflect God’s love and justice.

Roles in health, technology ethics, and environmental stewardship align with biblical values.

Need help discerning your career? Sign up for our free one-on-one impact mentorship here.

To read more about it click here.

Do you have any career uncertainties? Click here to read our article on three big career uncertainties you can trust God with.